Event Review/ Dream Day, Greeenpeace Yard, 8/23/14

For Bay Area aerosol art aficionados and devotees, there is no name more celebrated than that of Mike “Dream” Francisco. Even though the “computer style” designs of SF graf pioneers Crayone, Raevyn and the TWS crew were the first to gain national attention – when they were featured in Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff’s groundbreaking 1987 book “Spraycan Art” – Dream’s legend has surpassed that of any living Bay Area aerosol artist, with the possible exception of Barry “Twist” McGee (who’s become a gallery/museum exhibitor and no longer does much street work anymore).

For Bay Area aerosol art aficionados and devotees, there is no name more celebrated than that of Mike “Dream” Francisco. Even though the “computer style” designs of SF graf pioneers Crayone, Raevyn and the TWS crew were the first to gain national attention – when they were featured in Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff’s groundbreaking 1987 book “Spraycan Art” – Dream’s legend has surpassed that of any living Bay Area aerosol artist, with the possible exception of Barry “Twist” McGee (who’s become a gallery/museum exhibitor and no longer does much street work anymore).

Raised in the hardscrabble streets of East Oakland’s Sobrante Park neighborhood, Dream was a proud Pinoy who fell right in with hip-hop culture as it emerged from NYC boroughs and evolved Westward in the mid-80s. He reportedly studied East Coast graf masters such as Dondi – his trademark “D” bears more than a passing resemblance to Dondi’s version of the letter – but quickly progressed from imitator to innovator to master and mentor, especially to younger artists who frequented the “23” yard where he could often be found painting.

Raised in the hardscrabble streets of East Oakland’s Sobrante Park neighborhood, Dream was a proud Pinoy who fell right in with hip-hop culture as it emerged from NYC boroughs and evolved Westward in the mid-80s. He reportedly studied East Coast graf masters such as Dondi – his trademark “D” bears more than a passing resemblance to Dondi’s version of the letter – but quickly progressed from imitator to innovator to master and mentor, especially to younger artists who frequented the “23” yard where he could often be found painting.

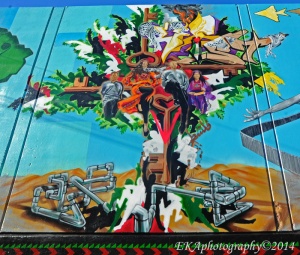

Dream’s art was instantly iconic, from 1996’s “Tax Dollars Kill” mural, to his 1993 portrait of murdered emcee Jesse “Plan Bee” Hall, to the backdrops he painted live for KMEL’s Summer Jam, to the numerous eponymous 3-D burners he authored. His maxim, “Dream… but don’t sleep!” became a rallying cry not only for aerosol practitioners, but for Oakland’s hip-hop subculture as a whole.

Along with Spie, his compadre in the TDK and Irie Posse crews, Dream ushered in a wave of political-themed graf which continues to this day in the Bay. Bay Area aerosol writers were rarely political prior to 1992, when Dream and Spie protested the 500th anniversary of Colombus’ “Discovery” of America with a series of works inspired by the “500 Years of Resistance” campaign uplifting the indigenous struggle. Irie productions often featured the numbers “1492,” a cryptic reference to the onset of colonialism. This led to a well-attended gallery show in 1993 at the Pro Arts Gallery (then located in Old Oakland), “No Justice No Peace,” which addressed police brutality in the wake of the Rodney King beating by LAPD.

It’s been a long time since that show, but I can still remember Dream arriving with the swag of a king dressed in royal finery, though in truth, he was attired in a generic vinyl rainsuit. That was part of Dream’s gift; he could make anything fresh.

In an interview conducted at the Pro Arts exhibition for the Soul Beat show “Hip-Hop Slam,” Dream explained his moniker: “I get most of my ideas from my dreams.” Graffiti, he said, was “something the mainstream just can’t deal with, so automatically, they’re gonna call it a crime.” The art show’s theme, he said, was a reference to police brutality and oppression, as well as the socioeconomic conditions in “East Oakland, and any other type of ghetto out there… every time i get hassled by the police, i gotta go out and do me a piece.” Spray-painting, he added, was an alternative to violence, while the art contained in the show represented “a dose of reality, something they ain’t never got before.”

An official member of the Hobo Junction crew — he designed their logo — Dream went on to do graphic design and ink tattoos, and worked at a t-shirt an airbrushing shop at Hilltop Mall for a while. Although he had developed a political consciousness, he never left the street hustle completely behind; on February 17, 2000, a dispute over a minor amount of marijuana resulted in him being tragically murdered in West Oakland, leaving behind an infant son, Akil.

An official member of the Hobo Junction crew — he designed their logo — Dream went on to do graphic design and ink tattoos, and worked at a t-shirt an airbrushing shop at Hilltop Mall for a while. Although he had developed a political consciousness, he never left the street hustle completely behind; on February 17, 2000, a dispute over a minor amount of marijuana resulted in him being tragically murdered in West Oakland, leaving behind an infant son, Akil.

For the past 14 years, Dream’s legacy and memory has been kept alive by the TDK Familia, his crew members and peers, who organized a celebratory event called Dream Day. This year, the event was held at Greenpeace’s yard in West O, on 7th St., next to the People’s Grocery. Not only was Dream Day a family affair, but it was a perfect example of the type of unique, iconic event which puts the grit in Oakland and the heart in the Bay Area’s hip-hop community.

After passing through the gates, and putting a little something in the donation box – proceeds benefitted the Dream Book Fund and the Dream Legacy Fund for Akil Francisco, now 14 – I stepped into what seemed like a hip-hop fantasy world. There were about a dozen writers painting pieces, in broad daylight; some had brought their families with them. A selection of top-notch DJs, including Sake One, DJ Fuze, Myke One, Max Kane, and Dulo Dulo, were spinning everything from Bay Area old-school hip-hop and mobb music classics to equally-classic dancehall reggae. Food was provided by the Lumpia Lady and El Taco Bike, and beverages ranged from water to beer to sangria to rum punch. Meanwhile, Marty “Willie Maze” Aranaydo, a Dream protégé who’s become a talented artist, DJ, and graphic designer in his own right, emceed the proceedings.

The vibe got even fresher, with live performances by Equipto of Bored Stiff (who rapped a song he wrote in honor of Dream) and Richie Rich, the legendary East Oakland rhyme-spitter and game purveyor, who did his classics from the 415 era, “415,” “Sideshow,” and “Groupie,” along with “Let’s Ride,” a Town favorite from his 1996 Def Jam album Seasoned Veteran. It was hella cool seeing all the fam up in the house, especially the older writers who rarely come out to events these days anymore. If you were there, you know exactly what I’m talking about, and if you missed it, you’re probably sorry you did.

The vibe got even fresher, with live performances by Equipto of Bored Stiff (who rapped a song he wrote in honor of Dream) and Richie Rich, the legendary East Oakland rhyme-spitter and game purveyor, who did his classics from the 415 era, “415,” “Sideshow,” and “Groupie,” along with “Let’s Ride,” a Town favorite from his 1996 Def Jam album Seasoned Veteran. It was hella cool seeing all the fam up in the house, especially the older writers who rarely come out to events these days anymore. If you were there, you know exactly what I’m talking about, and if you missed it, you’re probably sorry you did.

Dream’s legacy, however, stretches further than just an annual celebration in honor of his name. What Dream gave Oakland wasn’t just a folkloric legend of a martyred king to brag about in graf circles, but a legitimization of the aerosol artform and a sense of community engagement and social responsibility which extends to public art.

This can be seen in recent highly-visible works by members of the TDK Crew: the “StAy” mural featuring Rickey Henderson on 3rd St. (near Washington); Spie’s contribution to the Palestine Solidarity Mural Project on 26th (near Telegraph); and the “West Side is the Best Side” mural at 17th and Peralta painted by Vogue, Bam and Krash (which gives Dream a boxcar-style shout-out).

No doubt, were Dream still alive, he would be proud to see the graffiti aesthetic he championed – so underground and rebellious during his era – become more accepted, both in the art world, and by the community at large. -EKA