Guest Commentary by Adisa Banjoko, The Bishop of Hip-Hop

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said: “If you love the poor and bring them near you. . .God will bring you near Him on the Day of Resurrection.” – Al-Tirmidhi, Hadith 1376

As the sun rose February 2nd on the Bay Area, I called my friend Vince Bayyan about strategies to strengthen the national impact of the organization I founded, the Hip-Hop Chess Federation. I was concerned; street violence was getting too extreme and young people were just getting too comfortable with it, as opposed to resisting it head on. I felt like HHCF wasn’t doing enough, that I could do more outreach. After speaking with Vince, I decided I was gonna reach out to The Jacka, a well-known Bay Area rap artist I considered a personal friend who had supported the HHCF’s mission on many previous occasions, and talk to him about Vince’s plan.

I went to work and began teaching at my job in East San Jose, at ACE Empowered. I came home and not long after dinner, my wife brought me the laptop and said, “I think this just happened. I’m sorry babe.”

I got on Twitter, and “#RIPJacka” was rapidly trending. My heart sank like a stone. My stomach might have gulped, but if it did, I didn’t hear it. Damn. Another one lost to the streets. And this time it was a real one. There was nothing to do but say a prayer for my brother.

My friend was murdered a few days before my 45th birthday. Most of you knew him by the name he rapped by: The Jacka. His name at birth, however, was Dominic Newton. His Islamic name was Shaheed Akbar. Like most of his friends, I called him “Jack.”

The first time I met The Jacka, it was at San Jose State University in 2001, while attending a Hip-Hop Congress event. Shamako Noble, the organizer of the event and an amazing rapper and activist, had been telling me how important he was in the streets for some time. Shamako told me, “The Jacka is real street, but he’s serious about upliftment in the hood.” I thought he seemed like a sincere cat. Not your average “gangsta rapper.” But, as I later found out, it was way deeper than that.

To be honest, I don’t remember a lot about meeting him that day. But once we met, over the course of nearly fifteen years, Jack and I always stayed in touch. What I remember more than what we talked about on our first meeting are the conversations we had afterwards. His knowledge was deeper than surface-level opinions, book science or street game. It was an absolute fusion of the three. So he could speak one sentence about God and another about gang life in the East Bay and it all was immersed in the same pure essence.

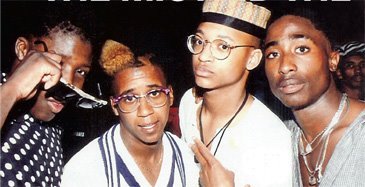

“I met Tupac in 1989 through our mutual friends Ray Luv and DJ Dizzie. Right up until his tragic murder in 1996, we developed a friendship that, while originally rooted in Hip-Hop, was much more about political and social activism. With The Jacka, it was the same kinda thing.”

Jacka will invariably be compared to other fallen Bay Area Hip Hop heroes: Tupac Shakur, Mac Dre, Seagram, Mike Dream, and the list goes on. I met Tupac in 1989 through our mutual friends Ray Luv and DJ Dizzie. Right up until his tragic murder in 1996, we developed a friendship that, while originally rooted in Hip-Hop, was much more about political and social activism. With The Jacka, it was the same kinda thing. Our friendship was focused on our faith. I don’t think he ever shared a lyric with me over the phone or played me a beat. Hip-Hop was almost off our radar. It never came up. Our focus was striving for oneness with God despite our flaws.

My initial introductions to both Pac and Jack were casual. But as I got to know each of them better, both relationships deepened. They became friends I cared about, people I knew not as rappers, but as human beings. Then, one day, out of nowhere, you look up and they are gone, dying as icons, legends, myths. Immortalized in death as they were celebrated in life. Pac and Jack were both lovers of the people, champions of those who have been ignored, and uncompromising in the expression of their art. This made them both equally feared and respected in life and death.

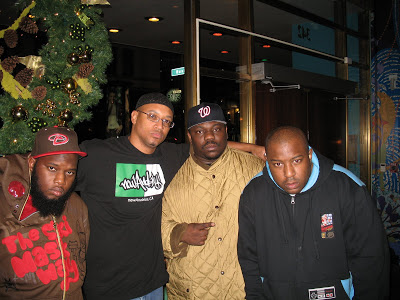

The last time Jack and I hung out, it was October 24th, 2012. Jack brought the Mob Figaz, the crew he started with back in the ‘90s, to John O’Connell High School in San Francisco’s Mission District, an environment which is often rife with racial and gang tensions. At O’Connell, Jack talked to some of the youth there about making wise choices in life and going after what is in their heart. He spoke as part of a panel that had graff artist Carlos Rodriguez, rapper Big Rich, Latino entrepreneur Pablo Fuentes and educator Arash Daneshzadeh. After the talk, Jack signed autographs and took photos with some of my students. His presence meant a lot to them.

“The Jacka’s knowledge was deeper than surface-level opinions, book science or street game. It was an absolute fusion of the three. So he could speak one sentence about God and another about gang life in the East Bay and it all was immersed in the same pure essence.”

A few years before that, in 2007, I connected with Jack, Freeway, and Beanie Sigel at the Triton Hotel in San Francisco. I interviewed them for a piece I wrote for Illume Magazine called “Thugs in the Masjid.” (Editor’s note: the word “masjid,” Arabic for mosque, is analogous to the word “church” in English.) What I remember most from the interview was that he wanted Beans and Freeway to shine. He actually spoke the least in the interview, but as always, he had amazing things to share. What stuck with me was his complete belief in the power of prayer.

Here’s an excerpt from our conversation, which illustrates the strength of his faith in Allah: “One day I got caught up in a high speed chase. I had to hop out the car, run, with my shirt off- everything. I kept saying “a-oudu billah min esh-sheytan nir rajim“. (Editor’s note: this translates to “I seek protection from God against the devil”) They let the dogs loose on me. “I was like, I got nothin’.” The dogs came out, but they never attacked… It worked.”

Before the interview, my friend Mikael Santini and I met the three rappers in the lobby and Mikael took at the time what I thought was a quick, insignificant photo. What I didn’t know was the picture was one of the first shots to document Islam uniting East coast and West coast rappers. This was actually a highly significant cultural moment in the Hip Hop world. Jack and Freeway went on to drop many more gems together, solidifying their bond and building on Islamic knowledge. On the Write My Wrongs Mixtape, released in 2013, the two even used a song featuring Malcolm X.

Jacka and I built on a lot of Islamic topics. No matter how much grime and street truth Jack shared with his fanbase, he always pointed people towards Islam. He hid his inspirational medicine for the diseases on the streets inside the candy of rap music. His deen (Editor’s note: “deen” is Arabic for religion or spiritual path) was to uplift the ghetto, from a ghetto perspective. It goes without saying that he kept it 100. But as thugged-out as his image was, he was always seeking knowledge, always looking for more jewels for his crown.

Once The Jacka asked me to help him find some books. He wanted to refine his relationship with Allah. So one rainy day, K9, Jack and I visited Rumi Bookstore in Fremont, CA. Jack bought “Purification of the Heart” by Hamza Yusuf, along with a few lecture DVD’s from Hamza and Imam Zaid. (“Purification of the Heart” is an ancient Islamic text from West Africa. It teaches people specific cures for ridding the self of vices like greed, anger, and other flaws that hold us back from being truly great.) Then we went to a halal restaurant. K9 and I played chess while Jack and I talked about religious matters. Jack was not a chess player. “I need you to show me, Deese!” he’d say. I promised him I’d teach him next time we hung out.

Not long after reading Hamza’s book, Jack made a rap about Purification of the Heart. In his 2009 single with Freeway, “They Don’t Know,” not only did he reference our conversation two years earlier when he said, “me, Beans and Adisa, we were building on Islam,” but he also worked the theme into his flow: “I tried to purify my heart, ‘cause I’m a slave to my thoughts/ I’m a monster out here, ‘cause I change when it’s dark.”

From that point forward, Jack and Freeway started dropping lyrical fire on the streets, squashing widely-held notions of coastal beefs with their inspired collaborations. Jack was wise to build alliances with other like-minded, independent artists who, like him, had heavy street reps. He connected with East Coast heavyweights Cormega (The Firm) and Raekwon (Wu-Tang Clan). He teamed with Freeway, Dungeon Family alum Killer Mike, and South Bay producer Traxamillion for the gem-laced “Sunnah Boys,” one of my favorite Jacka tracks of all time.

It’s difficult right now, while his passing is still so fresh in my mind and the minds of many in the Hip Hop community worldwide, to measure Jack’s total impact. I believe he taught more young people about the value of striving to live better through Islam, than a lot of the national Islamic dawah (outreach) programs combined. This is because he was courageous enough to take truth to cats deep in the street life. His music was an open hand, an attempt to pull his people up.

“Jacka and I built on a lot of Islamic topics. No matter how much grime and street truth Jack shared with his fanbase, he always pointed people towards Islam. He hid his inspirational medicine for the diseases on the streets inside the candy of rap music. “

Inside the American Muslim community, there have been longstanding arguments about Muslims doing music. This came up mainly because as many African Americans converted to Islam, they did not let go of their love for music. Many immigrant Muslims are more conservative by nature; many Arabs and other immigrants have been unforgiving in their condemnation of Muslims who make music. Nevertheless, the Black men and women of North America have always embraced music as a method to preserve their history, share wisdom and inspire.

Dr. Ivan Van Sertima’s book Golden Age of the Moor shows irrefutable evidence that African Muslims not only innovated music as they ruled Moorish Spain for five centuries, they invested in it (and other forms of culture) heavily. The Ottomans made similar investments. So, to me, it is no surprise that The Jacka held onto his music as he evolved in his faith.

It’s worth noting that the Chapel Hill murders of Muslims Deah Barakat, Abdi-Samad Sheik Hussein, Yusur Abu-Salha, and Razan Abu-Salha happened in close proximity to the murder of Shaheed Akbar, aka The Jacka. Oakland’s Lighthouse Mosque, led by internationally respected Imam Zaid Shakir, held a prayer vigil for all of them. The mosque released a statement listing them all as “young martyrs.” It read in part “May Allah grant patience and Healing to the grieving family who must now mourn their loss!”

When I read the statement, a tear of joy started to form in my right eye. I blinked long and hard to hold it in. The Prophet Muhammad taught that “The ink of the scholar was more holy than the blood of the martyr”. This shows that Islam loves scholars who share the truth above warriors who shed blood in God’s name. Prophet Muhammad also taught that the greatest jihad (struggle) is within one’s own self. The struggle to master one’s vices, passions, bad habits, etc.

Jack was never quiet about his struggles. That is what made him so approachable and impossible to judge. It’s what made his smile so infectious, his word so sincere. So many gangsta rappers and so-called revolutionaries talk about their love for the hood. But unless they have an album to sell, you might never see them on the turf in a week, a month, or a year. The Jacka was the exact opposite; he was always in the hood, mixing it up with his people. In retrospect, maybe he was there too much.

When my birthday came a few days after he died, it was pretty low-key. It rained heavy that night. The Jacka was on my mind the entire day. I was torn between feeling thankful to be alive, and feeling guilty that I was still among the living. Jack was only 37. Last year, I lost 5 people. It was too early in the year for me to be dealing with death, I thought to myself.

Meanwhile, scholars from all over the world were convening at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania to talk about Malcolm X’s impact on politics, art and spirituality in America and the world, for a conference called “Malcolm X 50 Years Later.” I had been invited by Dr. James Peterson, Director of Africana Studies at Lehigh, to give my insights on Islam’s impact on Hip-Hop through Malcolm X.

I worked for days to put together my presentation. But after learning of Jack’s murder, I tossed it all out and put together a new lecture: “Black Redemption: Detroit Red and The Jacka.” The discussion talks about how the young life of Detroit Red (Malcolm’s street name before Islam) and The Jacka’s young life before Islam were very similar. I went on to talk about how faith and art are common refuges for Black men when enduring oppression and exclusion from the American mainstream. My talk was received well by professors and students alike. Dr. Peterson and I spoke the next week. He told me all the lectures from the conference will be made into a book. It made me glad in my heart to know that Jack’s contributions to Hip-Hop and Islam will be preserved for future generations. The Jacka was no saint, but he loved the poor, helped a lot of people who could not return the favor and did it all for the sake of God.

How will The Jacka’s legacy live on? I think in the coming years we will see radio stations that ignored his work put him in rotation. We will see TV networks that would have said he wasn’t “newsworthy” two months ago doing documentaries on his life. Maybe people will try to make movies. I don’t know. I don’t even care. I just wanted to let my brother Shaheed Akbar know that I really did love him. I never felt like I was able to thank him properly for all the times he gave love to the kids, shouted me out on a track, or just called to say what’s up. Jack, if you’re listening, I will never let them distort your work to enlighten the kids on the streets, incarcerated youth and brothers on lockdown. God willing, I will teach you chess in jannah. Salaam alaikum akhi.

Adisa Banjoko is the Founder of the Hip-Hop Chess Federation. For more information on the HHCF visit www.hiphopchessfederation.com.