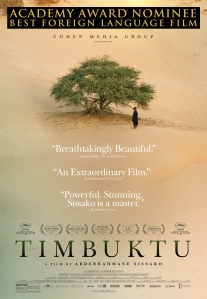

Film Review/ “Timbuktu,” opens January 30 at Sundance Kabuki, SF

Arriving at an auspicious time—after the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks in France and reports of a Boko Haram massacre in Nigeria have raised global concerns over militant jihadists—Mauritanian filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissoko’s sixth film, “Timbuktu”, offers a perspective largely missing from Western media reports: the indigenous African point of view.

The film, which opens January 30, details the arrival of an armed band of jihadists who occupy a Malian village not far from Timbuktu and declare sharia law. The film is primarily concerned with the impact of the jihadists on the village, whose peaceful existence is now threatened by violence, detention, and brutal punishments for such crimes as daring to play music. The main protagonist, Kidane, is a cattle farmer who lives in the sandy desert outside the village with his wife and daughter. Initially unaffected by the jihadists, he is drawn into the center of their conflict following a dispute over a cow who wanders into a river fisherman’s net.

The storyline is based on real-life events: a 2012 occupation of the fabled city by Islamic militants—many reportedly mercenaries displaced from Libya after the US-backed overthrow of Qaddhafi—which garnered a number of media reports in the Western press detailing how hundreds of thousands of Timbuktu’s historical artifacts and ancient documents were smuggled to safety.

The storyline is based on real-life events: a 2012 occupation of the fabled city by Islamic militants—many reportedly mercenaries displaced from Libya after the US-backed overthrow of Qaddhafi—which garnered a number of media reports in the Western press detailing how hundreds of thousands of Timbuktu’s historical artifacts and ancient documents were smuggled to safety.

There’s also a much larger backstory behind “Timbuktu.” The history of Arab incursion into sub-Saharan Africa is a long and complex one; Mali and Mauritania were both conquered by Arabs long before they were colonized by the French, and it’s not uncommon for Northwest Africans to have Muslim first names and traditional tribal surnames, as Sissoko does. Like the novelist Ayi Kwei Armah in “2000 Seasons,” Sissoko paints an unfavorable picture of Muslim conquest, but what’s interesting here is that what the audience is witnessing isn’t theological, but rather ideological, conflict. In the real world, Muslim violence is more often sectarian than not, i.e. directed at other Muslims, and, obviously, not all Muslims share militant fundamentalist beliefs.

Curiously, the jihadists in “Timbuktu” are given little backstory. We don’t know their motivation, nor whether they are part of a larger extremist/fundamentalist group. We are told that one of them, a translator—at various times, the film switches between Bambara, Songhay, French, English, and Arabic languages—is a Libyan, but that’s about all the exposition we get on the group’s origins. The jihadists aren’t quite faceless, but they aren’t exactly three-dimensional, either. We learn that one of them smokes cigarettes, implying a hypocritical morality, but while Sissoko avoids the clichéd stereotyping a Ridley Scott or Michael Bay might have brought to the material, he doesn’t supply his antagonists with much nuance. There’s no ambiguity in how the jihadists are portrayed—as violent, morally-suspect men who justify their actions through a flawed interpretation of the Qu’ran.

Born from a Malian father and Mauritanian mother, Sissoko—who currently lives in France—knows the territory he covers well. “Timbuktu” is far from “Black Hawk Down” or movies of that sort, which fetishize and exoticize Eastern culture from a xenophobic, culturally-imperialist lens. Sissoko takes a cinema verite approach, often capturing a documentary-like feel in his depiction of life in a Malian village.

In one of the film’s strongest scenes, a group of youths pantomimes playing football (soccer) after the jihadists confiscate their ball. There’s no dialogue, but the visuals communicate volumes—about the ritualistic African football culture and the need of the people to maintain their rituals. In another powerful scene, a young woman sings a beautiful traditional song as she is being publicly lashed for daring to play music with members of the opposite sex.

“Timbuktu”’s pacing is slow and measured. Sissoko’s approach to directing is sparse and minimalistic; There’s none of the frenetic jump-cuts or contrived suspense we’re accustomed to seeing from major film studios, and the cinematography is simple yet effective, with lots of wide shots capturing the expansiveness of the desert’s curved, roundish sand dunes. The tempo makes viewers consider the landscape and the environment more carefully; the film soaks up the natural lushness of the Malian countryside. Its soundtrack also captures Mali’s wonderful-sounding indigenous music, often said to be the foundation of blues.

One of the major themes in the film, besides that of cultural displacement, is juxtaposition. The opening montage juxtaposes an antelope running across the plains with a Jeepful of armed men, shooting at it. The beautiful shots of nature and of the villages’ traditional terracotta architecture are offset by calm-shattering acts of violence. The brutal punishment of an unmarried couple is contrasted with a scene showing one of the jihadist leaders practicing yoga. The jihadists have modern accoutrements—Toyota trucks, motorcycles, and AK-47s—while the villagers are mostly traditional, save for their cell phones. In the final montage, the antelope metaphor returns, but this time it’s alternated with shots of a young girl escaping her pursuers.

The very un-Hollywood ending is both sobering and somber. There’s no 4th act deus ex machina, and the villainous jihadists never get the comeuppance you’re left hoping for. “Timbuktu” resonates strongly as more a plea for help and return to traditional cultural norms than political propaganda. However, given the current climate, the film may actually inflame anti-Islam sentiments among Westerners, despite its emphasis on distinguishing between perpetrators and victims within the Muslim faith. Still, for devotees of African films and those with enough of an understanding to digest cultural nuance, “Timbuktu” is well worth seeing.